Interview

by Nick Tsoutas

2008

Brad Buckley in conversation with Nick Tsoutas

An edited version of this interview was originally published in Brad Buckley Monograph (Artspace, 2001)

NT

Brad, perhaps this could be more conversional, rather than an interview. I understand that you originally began as a sculptor where the emphasis of your work was on the object but over the last twenty years or so, your work has become more ephemeral, more installation, more architectural and site specific. Could you discuss the influences that caused this shift from the discrete object to installation.

BB

Fine, lets talk. It’s funny but I have never really considered myself a sculptor, rather an artist. Like many artists my education and life took various twists and turns ranging from a foundation in design and then moving through film and video before I began seriously making art.

My first exhibition was in Sydney at the Sculpture Centre in 1973 which at the time was one of the very few venues that would show performance or experimental work. In this show I had a number of large objects fabricated in soft plastic that were filled with coloured water and came down the wall spreading out over the floor. I remember Daniel Thomas reviewed the show and mentioned that some of the art was leaking, which it was, as I arrived at the opening. [ Laughter ]

At the time, the Sculpture Centre was an important venue for the development of contemporary art in Sydney, I first met Ken Unsworth and Bruce McCalmont there in the early seventies – it was a meeting place, a place that artists could meet – something that we don’t have now. It certainly is a period which is not really understood and one which should be fully researched by an aspiring scholar of Australian art.

Anyway, even these early objects probably had some relationship to the site as I was quite conscious of the scale of the gallery while making these sculptures. After having two more exhibitions I felt the need to leave Australia and in 1975 I went to New York and Europe, spending the next nine or ten years travelling and living in various places. I think that being away from your own country gives you a certain freedom, anonymity perhaps, and allows time for reflection.

During 1979 I decided to continue studying and attended the postgraduate course at St Martin’s School of Art in London. This was a formative experience as I discovered that many of the negative aspects of Australian culture were in fact the residue of that society. In contrast to that experience, the time I spent in the States undertaking a Master of Fine Arts at Rhode Island School of Design and then later as an Australia Council Fellow at PS 1 The Institute for Contemporary Art in New York, offered possibilities to live and work in a culture that continually sees opportunities. I think that I was also fortunate to be at RISD during that time because of a special mix of students and faculty, particularly Professors Lauren Ewing and Richards Jarden.

It was probably at this point that I actually began making installations, building works which were influenced by a range of ideas that I had been exposed to over the previous decade but had their intellectual origins in the milieu of my family, particularly my Father, which I would describe as secular humanism.

NT

What are the main characteristics of that change and what is it that constitutes installation as opposed to object based activity.

BB

Well, a fundamental experience I had while living in London was seeing Happy Days by Samuel Beckett. I remember walking out of the theatre and realising that a number of conventions I held about the nature of art in our culture had just been profoundly challenged.

So, this shift which I think was gradual, rather than a conversion on the road to Damascus, was my search for a way to make art that used fragments, clues or pieces and my interest could be termed intersubjectivity. So that one actually builds or puts together over a period of time the parts which led to an experience of the work which is more speculative and where the audience has an extended experience or exchange with the work.

NT

In the recent work you transform space, the work seems to be increasingly more lucid, one almost has the sense that the space is disappearing. It’s about a certain otherness in terms of art practice, a different metaphysical or psychological space that doesn’t rely on the constructs of art as we know it.

BB

As we know it – I am not sure about that – however whether the work is inscribed on an existing site like the High Court of Australia or a work that exists in an authorised space, that isn’t really the issue, it is not a critique of an authorised place to display art. But there is a critique of the place or site that the work is actually operating in, this is an important distinction. This is one reason for using different colours as it is a strategy for colonising the site or occupying the site. When there is a unifying layer of colour over everything it negates the idea of material, everything takes on the same value because it’s all yellow, red or black. The space starts to operate in a particular way which I have referred to in the past as the eroticisation of space. So, now when you enter the space it is a phenological experience because you are surrounded or engulfed by a particular colour, altering your experience of that site and thus defusing its subjectivity.

NT

The theatricality of the work is another interesting aspect, as is your reference to Beckett. Some theoreticians consider Beckett to be an early deconstructionist or postmodernist. In light of this I was wondering if you could comment on the role of the formative and on the illusive subject in your work.

BB

I have always been very eclectic in what I read and which artists that I find of interest. However Beckett’s writings have been influential on my thinking, as have a diverse group of other writers and artists ranging across various disciplines from Marcel Broodthaers, Artaud, Milan Kundera, James Joyce, Lawrence Wiener, Vaclav Havel, Michel Foucault, Kawabata, Lauren Ewing and Xavier Herbert and so on. It was through the writings of Beckett and others that these ideas about art made me consider what was art’s place, what was its role. If art wasn’t a cut out, if it wasn’t a prop for some representation of what goes on in the world but in fact it was itself and spoke of itself, then one is faced with a very different set of problems.

These issues percolated through the work over a very long time driven by an interrogation of what is knowledge or what is the truth and that stems from a whole range of experiences that I consider were formative in my early adulthood. It comes from a very pragmatic sense of what you’re told and it raises the question ”Why should you believe what you are told?” From this developed a more complex project, where I am tearing away at what is acceptable knowledge and that the given, why it’s given and how it is used has a certain impact on the operations of our culture. Of course this questioning or considering the truth in a philosophical way is a recurrent preoccupation in our intellectual tradition and here I am thinking of Socrates and his journey towards knowledge without the expectation of finding truth or Nietzsche who spoke of no absolute truth through to the more recent ruminations of the continental philosophers.

NT

What about reception, the role of the actor and the spectator. Your work seems to direct the viewer in a very actorly way. They have a certain role to play, they have a certain role by which to perceive things. It’s essentially experiential and the body itself is implicated, the body is a site, is that an integral part of the work?

BB

Yes, these are important issues and I have been thinking about reception and the role of the spectator for some time but I don’t consider the body to be a site in the sense that I think you mean it. Rather, I am concerned with how the work impacts on them, what is the horizon of expectation of the spectator. There is a strategic position that utilises a shifting of time and space in the installations, moving the spectator around or down the work through a series of possible viewing points. This has to do with the way we operate, how we see and how knowledge is transmitted and assimilated. So, rather than having a solitary iconic object which you contemplate, you might know the installation in a different way from another, depending on how you have chosen to travel or move through the work.

NT

Your installations seem to present the spectator with a dilemma or contradiction insofar as they simultaneously suggest: a desire, a seduction, a sensorium or hidden emotions. They are in fact desirous but they also present the viewer with a sense of untouchability and what Jean-Francois Leotard refers to as “a sacred silence” because it touches upon the untouchable and a separation between the inside and the outside that seems unequivocal. Would you care to comment?

BB

Yes, of course. However, I am more familiar with Michel Foucault’s comments on the importance of silence and I think he suggested in his last book that we reinvent a culture of silence. I think that art competes for its place in the world with the media, technology, film, video, the net even though at times art may incorporate all of these into its production. Perhaps by stripping or emptying out the objects and extraneous things I am creating a space which is silent. In this silence there is the possibility for contradiction or revelation because there maybe many different types of silence, a silence of love or a silence of aggression, this is what I believe you are referring too.

NT

I understand the emptying out but the work does seem to operate in a zone outside of itself; its otherness. Almost like the space that the work is located in is not the space that the work operates in.

BB

I have spoken often about the unknowable in my work – there is always a tension – a tension with the wider society because contemporary art always fails, it does not deliver what people expect, it does not represent something which is familiar or known and so, this otherness that you have identified is partly a result of the continuing conflict created by a search for the subject. In this search one begins to look beyond the work, seeking meaning or openings and this maybe what produces this sense of slippage.

NT

You spoke before about the milieu of your family and of course I am aware that your Father, Jim Buckley was a prominent figure, or identity, in Sydney during the Push years as the proprietor of the Newcastle Hotel in the Rocks.

BB

Yes, yes, actually lower George Street as The Rocks begins at the Cahill Expressway.

NT

Of course, yes – but the Push was characterised by libertine values, preempting the permissiveness and anti-authoritarianism of the 60s. Did this radicalise you and in turn do you see your work as a radical gesture?

BB

I guess that if your world is populated with people of such varying and diverse attitudes it is only later when I began to realise that this was the exception to the rule, that I was surprised by the narrowness of Australian society. John Conomos has described the Newcastle Hotel “as a libertine island in a sea of Anglo-Saxon repression”. So, no it did not radicalise me as it was my world – my experience – but rather it did offer models of tolerance, social justice and a critical framework for considering the world. It also introduced me to the idea of the show pony and stirrer, two concepts that I have always found very useful, especially when dealing with curators, Nick. [ Laughter ]

NT

But do you think your work is radical.

BB

Radical, it is an interesting word. The neo conservatives now talk of their radical agenda, a type of post-Thatcherism. No, no, not radical because radicalism is tied to modernism and this project has played itself out, it does seem to be exhausted. What it does offer is the possibility of a particular relationship to the culture that I am part of and which I understand as having its origins in the Western intellectual tradition.

NT

A number of writers have discussed your work in Lacanian terms and have cited George Bataille as an influence. I suppose that I am edging towards the sexual aspect of your work and the role of language in your installations.

BB

Perhaps I will discuss the use of language first. It was inevitable – I guess – because of the influence that literature had on my thinking, my interest in Fluxus work and the currency of conceptual art at the time. I suppose that text first appeared in my work as captions in the 70’s, rather than titles, as I considered that all material produced including the announcement cards, artist’s notes, catalogues and fliers, were part of the work, they extended the work, in a physical sense beyond the site, they became another site. Not that I fully understood that at the time.

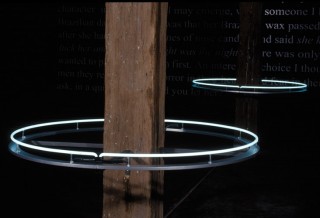

I think that one of the reasons I began using text is because culturally it is understood to have explicit meaning. That the expectation for most readers, despite the best efforts of the deconstructionists, is that the text will give itself up, revealing a particular meaning. So it was through using neon as a single word or in short phrases, incorporated into various installations from the early 80’s that I used the text to play upon these cultural assumptions.

As the lexicon evolved the text began to operate not as a single word but as a ribbon, band or stripe diverting you, acting as a mismarker – like a slip of the tongue when we are in conversion – allowing for various forms of reception rather than one simple experience, there is not a single way of knowing the work, there is no clear answer.

NT

And what of the influence of Lacan or Bataille and the sexual aspect of your work.

BB

What influences me is diverse, ranging from Realpolitik, theatre, history, art, philosophy but of course both of these writers are important, they are important to me and it is worth remembering that Bataille was writing in the 1950s. Unfortunately, during the last decade or so, they have become trademarks – intellectual trademarks, a way of indicating authority – the great subtlety and genuine invention of their ideas is often reduced to dogma. And when there is a general intellectual malaise and raising conservatism as we have at present, one of the first casualties is always going to be the unfamiliar or difficult. Look at how contemporary art has retreated to a dumb formalism, where artists proclaim that they don’t read or know about history, they don’t engage in or even understand the politics of their society. This evacuation of politics from art, and some would say life, is a very dangerous state of affairs for any society but in a relatively new or evolving place like Australia, it has profound implications.

As for the sexual aspects of the work I suppose that I am primarily concerned with the tools [ Laughter ] that society has developed to maintain a particular structure. One of the most enduring in the West is its control and prohibition of sexuality and its discourse, that is, how we may speak about sex. I don’t think that there is a particular sexual aspect to my work, not in the sense that you are alluding too, it’s not the subject – it is a veneer, sometimes – perhaps at others times this veneer is overtly political.

One of the reasons that I often return to it, the sexual – sexuality does seem to get people rather hot under the collar – is because I am continually surprised at the depth of this sexual prohibition even in rather liberal societies like Australia. The other strange thing is that the handmaidens who prosecute this prohibition with great relish are often those who are themselves marginalised but who seek entry into the mainstream, perhaps they believe that oppressing those who don’t conform to this new orthodoxy will enable them to move to the centre.

So, the issue of sexuality could be understood as desire, eroticisation, excess and seduction as they all play a role in the work. At times this may seem overt, at other times, vailed or concealed. Perhaps the works turn back on themselves in some way, offering a transgressive relationship with the viewer or spectator, creating an agency of exchange that implicates him or her, in more than just looking.

NT

This veneer, how does it operate when you consider the flag work in Israel – this space between the intention and reception of the work – you made a very radical…

BB

Provocative is better, I think.

NT

Alight provocative – it’s almost like cutting – that work is very different from the works that exist in the galleries. It puts one in the situation of being forced to address or respond to, not just the cerebral or mysteries of how the gallery operates but you are forcing a confrontation. Every time the flags flutter, one goes in microseconds from the altered images of the Palestinian flag and then to the Israeli flag and back again.

BB

Sure it is provocative, yes it is but the same strategies are operating in all the work and the flag piece is no different. This is what I am talking about, the veneer, it is only a veneer.

In Israel, when they invited artists, it was the Year of Peace, 1995 and the borders were open with Jordan, there was headway with the Palestinians. So, taking the signs of national identity and transposing the colours of both countries’ flags and then flying them next to each other seemed a critical way of dealing with that situation.

That work affected a number of artists who had come to Israel, who had not thought about making work that engaged in the politics, suddenly there was an outbreak of work that addressed this whole question of Israel. So, I think the work had a very particular impact on many artists and certainly on the local audience. It is the way in which the agent provocateur opens up broader questions about humanity and social responsibilities.

NT

In Australian art you are actually a very different kind of artist because you have situated or located your practice decidedly in an area of non commodity. You are almost indignant about the whole idea of selling art and you don’t make work for sale. You make large scale projects that you invariably have to fund. Not a very easy or enviable task and in a world that is increasingly commodified is there any room for otherness. You don’t have a gallerist or a dealer. You don’t make multiples to generate an income. It’s almost a purist attitude to the making of art.

BB

You make me sound like a Marxist or priest! [ Laughter ] As for the dealer question perhaps in a European context I probably would have a gallerist. I’m not necessarily opposed to selling things – it is not a political position – in as much that it is not a critique of late Capitalism. I don’t think that governments should own banks, airlines, insurance or communication companies, they should not be involved in commerce but they should be concerned with questions of education, culture, democracy and social justice for all the citizenry. I have always found the first democracy in Athens an important ideal and as you would know, democracy is the Greek word for the rule of the people and in this Athenian model of democracy all the people voted on every issue. So the contemporary way of considering this would be that governments would outline the issues on the internet and the citizenry would push a button voting yes or no, thus giving the politicians a direct response to their policies. I suppose we still have an anorexic form of this in referenda.

So, anyway, it is not a question of denigrating artists because they sell work, that would be very puritan. I do feel however that I have a certain latitude because I am not constrained by the need to consider the market, I am not interested in public art or producing artefacts for collections. This position, as you have so clearly identified, does have certain problems which includes funding but I suppose I made that choice and it has always allowed me to pursue my project with a sense of intellectual integrity.

I suppose it is the discursive nature, or inquiry that is paramount and this is augmented by an interest in the institution of the art school. I guess that I have a certain fascination with this pedagogical relationship which I consider important in the development of our culture, in the broadest sense. Many of the issues which are central to my work are also important in the context of the education of artists. Of course this is really a much larger question and perhaps we could explore it at another time but I do wish to stress how important I believe this relationship is between the two areas.

NT

That’s the point that I am making, you made a very calculated choice.

BB

Okay, although I don’t think it was calculated, more a maturing process that led to a position where I am not in any way inhibited by the market, the gallery system or reliant on ones capacity to produce artefacts. And once you understand this, understand that critical discourse maybe realised through various strategies, this is what I find compelling as an artist. Remember that I have been involved, over the past twenty years, in a range of projects including broadcasting of a critical arts programs on radio, convening forums and the editing of various publications. All of these activities are interconnected, they are not separate, from my work as an artist.

NT

Given your comments what will be the role of the artist in the future.

BB

Yes, sure – this is an important question – the role of the artist has evolved over the past hundred or so years for various reasons. One reason for this change, which is rarely discussed, has been the effect of the changing nature of patronage. For many artists the funding source of the museum, international survey show or that important collection is of little interest. They are not concerned with the moral or philosophical implications of where the support originated. And at the same time there is an ever expanding conservatism affecting public funding, whether it be the Australia Council or the National Endowment for the Arts in the States. Of course, the push for contemporary art to find support from the globalised corporate sector, who are primarily concerned with their image, is a perilous exercise. This situation creates the climate for repression, with artists imposing a type of self censorship, as they strive to be included in this corporatised society. In this climate art can easily be reduced to little more that a functionary of trade or foreign policy of the ruling government. John Ralson Saul has recently commented on this corporatising of the citizenry where the individual is expected to have an allegiance to the special interest group or corporatised sector but real democracy carries with it the responsibility to act for the civil good and not to conform or be obedient to narrow interests.

It is of some concern that much art which has been valorised during the past decade by corporatised museum culture proclaimed that it was only about one idea, or even better, about no idea. Here the artist gives up the role of a citizen – becoming a stooge, clown, dandy or flaneur – gives up public debate and criticism, and is thus rewarded for their loyalty and silence by the special interest group.

I do however remain optimistic as I think that the role of the public intellectual, writer and artist, as a group who understands that our culture and fragile democracy, can only advance with continual criticism of the various ideologies that now dominate our society. I do consider that this is one of the roles of the artist – it is my role – to be engaged in the culture, a participant or agent provocateur, I guess a stirrer.