The Slaughterhouse Project : The Light on the Hill

2002

Visual Arts Gallery, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA

Paint, neon, vinyl text, continuous audio, installed over two rooms, dimensions variable

Author of Princes Kept the View

Brett Levine is the Director of the Visual Arts Gallery of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is the former Team Leader, Collection Programmes, at the Dowse Art Museum in Lower Hutt, New Zealand. His essays have appeared in Object, Art New Zealand, Urbis and RealTime, among other publications. He now concentrates on contemporary practices, time-based media, and critical writing projects. He is the Series Editor of the Pocket Art Editions, which was launched in 2007. He lives and works in Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

2002

Brett Levine

Tom said to himself that it was not such a hollow world, after all. He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it — namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain)

If one were to adopt a late capitalist term to describe Brad Buckley’s mode of artistic production, it would likely be vertical integration. Instead, understanding his intentions more closely, I propose the term seamless. I begin here because The Slaughterhouse Project: The Light on the Hill, Buckley’s most recent manifestation of his ongoing series of interrogations, is one in which the closest attention to detail is required. In particular, the complexities of language, with all its inherent elisions, slippages, and parapraxes, from Freud to de Sausseure, to Lacan, Barthes, and beyond, must be considered closely.

The Light on the Hill is the title of Buckley’s early 2002 installation in Birmingham, Alabama. In a town marked by its complex bookends (which one might consider at one limit to be Dr. Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, and at the other Birmingham local Ruben Studdard’s recent elevation to “American Idol”, whatever that might mean), The Light on the Hill stood as both a symbol and a symptom.

As I have noted previously1, Buckley’s project is marked by the referential and symbolic significance of every stage of the process. From the invitation through the installation to the documentation, catalogue, and essay, each element of the project both presents and represents a unique aspect of the work. For The Light on the Hill, Buckley utilises a quote from Ben Chifley, Labor Party Prime Minister of Australia from July 1945 to June 1951. Buckley’s recontextualisation of this text stems in part from a reconstruction of the readymade2. Recognising, as Marcel Duchamp does, that a tube of paint is a readymade, Buckley applies this test to text. He then utilizes the text in a distilled form, which results in what one might term an “adaptive re-use.” In a speech to the Labor Party Caucus on June 12, 1946, Prime Minister Chifley said, in part,

I try to think of the Labour movement, not as putting an extra sixpence into somebody’s pocket, or making somebody Prime Minister or Premier, but as a movement bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people. We have a great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand. If it were not for that, the Labour movement would not be worth fighting for.3

What is unique is that Prime Minister Chifley’s observations, still regarded as a cornerstone of Labor Party policy, were closely resonant with the observations of a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., only a few short years later. Yet what Buckley’s invitation did, purposefully, was highlight a social and socialist agenda that was both antithetical and an anathema to much of the Birmingham population. From the outset, The Light on the Hill highlighted the degree of complexity with which Chifley’s social humanism stands against a southern American political system commonly marked by conservatism, “compassionate”Christianity, and high capitalism.4

In Tarrying with the Negative, Slovenian cultural critic and theorist Slavoj Zizek outlines the conditions under which national ideologies are often reinvented. In a chapter entitled, “Enjoy Your Nation as Yourself,” Zizek discusses how a fascination with the ‘Other’ is manifest precisely through the ‘Other’s’ ongoing reinvention of the then decaying cultural or social models of the dominant regime. Zizek continues, suggesting that the Other’s surplus enjoyment, their jouissance, that stems from this reinvention, becomes the motivation for their persecution by the dominant regime.5 One could argue that Zizek’s analysis transfers subtly to contemporary southern cultural life.

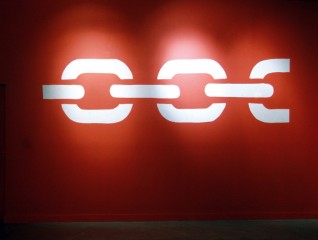

What The Light on the Hill does, then, is to create an architectural and social space in which these apparent antagonisms can be critiqued, discussed, and deconstructed. Architecturally, The Light on the Hill consisted of a two-room installation and a sound composition that served to unify the two. In the first room, Gallery visitors entered the frosted double-glass doors to encounter fire-engine red walls with white wall paintings. The rear wall of the front room consisted of a line drawing of a watchtower, while walls to the right and left encircled and enclosed the viewers with chains. Intriguingly, few viewers seemed to realize that in precisely the moment they entered the installation, they had become chained within it, but subject of and subjected to an experience of confinement and restraint. One need only recall here Swiss-born philosopher (and author of The Social Contract) Jean Jacques Rousseau’s famous pronouncement, “Man was born free, but everywhere he is in chains.” In the south, in particular, this observation has particular resonance. For Alabama was, historically, one of the states that allowed the ownership of slaves.6 What is more complex, however, is the question of the role of chains – here one must consider the fact that in Buckley’s installations, the most obvious reading is not necessarily the most relevant.

The other, more complex reading of the chains resides in their symbolic function of the organizing strictures of culture. Here, one might think particularly about Friedrich Nietzsche’s formulations of religion as repression which he proposes most comprehensively in his Genealogy of Morals. The theme of a passive Christianity which stands against his revaluation of values becomes a recurring discussion, emerging in Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist. There have been recent discussions regarding Nietzsche’s constructions of the value of slavery, many of which assert that his stand is not against the condition.7 A reading which equates commodity capitalism and subservience to slavery would certainly not fall outside Nietzsche’s ambit, and would appear, in fact, to be consistent with his revaluation of values. The Nietzschean construction of slavery which sees its value must lie closely aligned with his general opposition of overman and herd, of those capable of revaluing values for the construction of a stronger society versus those that, for whatever reason, are not. In this context, one might insert any number of signs for Buckley’s watchtower. Here, it stands merely as a trope, capable at its simplest level of signifying itself, but more capable, under consideration, as standing for those organizing principles, often self-situated, which enslave humankind.

It is possible to interpret the chains as the conditions through which the more radical elements of cultural control are maintained. Picture a society in which the purpose of confinement is not to keep others out, but to maintain what is within. This is a common notion in science fiction, but the most recent model of a closed society generally is the Western perception of the Communist bloc during the cold war. For this reason, when Buckley paints the front gallery red and the back gallery black for The Light on the Hill, one would almost certainly recall Le Rouge et le noir, by the 19th-century French author Marie-Henri Beyle, more commonly known as Stendhal. The author tells the story of Julian Sorel, a young man about to be put to death for a murder that resulted from a crime of passion. Consisting of a series of constantly shifting vignettes, The Red and the Black ultimately critiques the complexities of French urban and rural cultures, as well as the intricacies of a highly strictured religious and political realms.

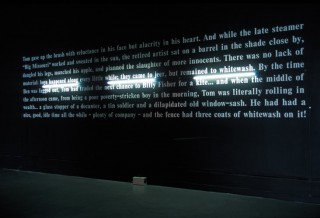

What is more intriguing in The Light on the Hill is what one might term, to paraphrase Roland Barthes, the presence of the text. For the text, as an idea, is made manifest again and again. From Chifley’s quotation which positions the invitation, to the allusion to Stendhal suggested by Buckley’s choice of colors for the installation, through to the edited text which adorns the second room. There, one finds an edited text from Tom Sawyer, which read:8

Tom gave up his brush with reluctance in his face but alacrity in his heart. And while the late steamer “Big Missouri” worked and sweated in the sun, the retired artist sat on a barrel in the shade close by, dangled his legs, munched his apple, and planned the slaughter of more innocents. There was no lack of material: boys happened along every little while; they came to jeer, but remained to whitewash. By the time Ben was fagged out, Tom had traded the next chance to Billy Fisher for a kite…and when the middle of the afternoon came, from being a poverty-stricken boy in the morning, Tom was literally rolling in wealth…a glass stopper of a decanter, a tin soldier and a dilapidated old window-sash. He had had a nice, good, idle time all the while – plenty of company – and the fence had three coats of whitewash on it!

What we encounter here, through the quote, is the miracle of commodity capitalism. For Tom, in an incredibly complex paradigm shift, exchanges undesirable labour for value, transforming it from an event he despises to one for which he is paid. In fact, people seem to line up for the privilege of performing the task. This is, perhaps, more insidious than the simple movement of capital, something that is more intriguing than the idea of surplus value being created through capitalism. For in the former, the surplus value is created by the disparity between wages, production, and surplus value. In the traditional Marxian system, a person sells labour for wages. In Tom’s case, he sells the opportunity to do labour – does no labour himself – and receives payment. In the end, the difference stems from the fact that the product of Tom’s labour does not necessarily create an object with surplus value that is the subject of market-based commodity exchange. At the same time, it does serve as a model by which people purchase “opportunities”, a term for which we could, perhaps, substitute the word markets. Or, instead, what the German philosopher and postmodernist avant la lettre Walter Benjamin would term “the dream world of mass culture”.

The second room, which contained the recontextualised, readymade quote from Tom Sawyer, was painted black from floor to ceiling. The work was lit with three cool white neon tubes which divided the text in half horizontally. Given the absence of color in this section of the room, one might consider notions of “blackness”. Particularly in the south, it is difficult to consider the idea of “black”, and almost impossible to utter the word. Buckley’s appropriation of text from Tom Sawyer, a text that in its original is difficult to quote from because of its language, is complex in and of itself. For those who do not know the work, it recounts stories of life on the Mississippi. It is perhaps less iconic than its counterpoint, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which tells a story of a journey. Regardless, Twain’s analysis of consumer capitalism is exquisite. He observes, wryly, that desire is directly correlated to attainability.

In The Light on the Hill, the unattainable objects are myriad, but may be distinguished by whether they are personal, physical, social or economic. For Buckley’s installation deftly critiques and makes visible each in precisely the same moment. The chains, discussed earlier, do mark physical boundaries, but they also delineate social, cultural and economic boundaries. In a “New South” determined to repress, if not erase, its complex history which bubbles just below the surface, it is difficult to separate any particular chain from another.

What unifies the seemingly disparate rooms into a seamless whole is partly the presence of a soundtrack. Comprised of two versions of All Along the Watchtower, pitch shifted and beat matched to mix seamlessly, Buckley takes viewers upon an ongoing journey of desire and defeat.

Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower first appeared on his John Wesley Harding album in 1967. At the time, Dylan had virtually disappeared from the popular music scene as the result of a motorcycle accident. Having left as the mystical minstrel of the epic double-album Blonde on Blonde, Dylan returned as a a country-sounding, ballad-singing troubadour reminiscent of his early-sixties folk days. What was particularly interesting about the 1967 release was Dylan’s wry construction of an identity. For in releasing the album, Dylan had created a simulacrum for the real Western outlaw John Wesley Hardin, a thug so mean it is suggested that he once shot a man for snoring. Whether it was intentional, or a mistake, it constructs a fascinating result. For by creating the fictitious Harding, almost someone else but individual in precisely the same moment, Dylan embodies French cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard’s reading of the simulacrum.

I begin here because the interweaving of Dylan and Hendrix raises a number of interesting questions that in many ways mirror the complexities of southern social and cultural existence. Dylan, as John Wesley Harding, sings words that recall the quest for Manifest Destiny, America’s reach across the western plains and the Rocky Mountains to colonize the entirety of what was to become the United States. In that guise, Dylan’s plaintive song recalls a heroicism that is unexpected at that time.

The song reads, in part:

“There must be some way out of here,” said the joker to the thief,

“There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth,

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth.”

Contrast this version to the one sung by Jimi Hendrix, which appears on his 1968 album Electric Ladyland, which rises to Number 1 in the US. When situated in the American south, particularly in Alabama, the song takes on an entirely different meaning. Recognizing the ongoing process of subjugation, the song stands as a call to action. Its roots then stem not from the folk tradition it would adopt were Dylan to sing it, but instead from the tradition of American gospel. What seems unusual is that the language and syntax apparently remain the same, but the Hendrix version of the song has much more in common with Negro spirituals. What is most significant, in relation to the iconography of The Light on the Hill, is that the transference of meaning towards the gospel/spiritual realm places the song in a lineage in which songs directly refer to freedom. One might consider here songs such as Wade in the Water, The Gospel Train, or Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.9

By mixing the two together, Buckley creates a situation in which the desires for the older South are joined in an oscillating relationship with a desire for the opposite. While I do not in any way assert that Dylan’s version is one which calls for a return to conservatism, it seems evident that the lifestyle outlined by the concept of “John Wesley Harding” and its implications appear at odds with the gospel spirituality of the Underground Railroad and the Hendrix versions.

This is an astute perception by Buckley, and characteristic of his understandings of reception theory. In The Light on the Hill, Buckley transcends accepted stereotypes of southern culture to inscribe upon a site a complex suite of differing political, social and ethical concerns.

Finally, there is the question of freedom, of movement, of restraint. If one reads the text from Tom Sawyer as representative of modern global capitalism – as the creation of a market economy in which it is desire, and not commodity, which are both traded and fetishized – then The Light on the Hill stands as a critique of precisely this movement. It recognizes the fact that global capitalism, particularly goods, services, information and property, moves unfettered at precisely the same moment that the movement of people is more and more restricted. Buckley recognizes that despite apparent changes to the social structures of contemporary culture, particularly those of the American south, it is as if the freedoms suggested are entirely in opposition to those which have been attained. One might think here of Zizek’s introduction in Tarrying with the Negative, where he observes:

It is difficult to imagine a more salient index of the “open” character of a historical situation “in its becoming”, as Kierkegaard would have put it, of that intermediate phase when the former Master-Signifier, although it has already lost its hegemonical power, has not yet been replaced by a new one.10

The Light on the Hill recognizes precisely this same openness. For if the South, if Birmingham, Alabama, stands as a site without a Master-Signifier (although for a number of reasons I doubt this is the case), then this openness stands as its only option.

I am reminded of a pair of Works Progress Administration-era murals that adorn the entrance foyer of the Jefferson County Courthouse in Birmingham, Alabama’s largest city. To the left, a man reminiscent of the Russian-born, American immigrant author Ayn Rand’s Howard Roark – suited, strong, social(ist) realist, standing over a city of men working towards an industrialized future. On the other side, a dark-haired Southern belle, antebellum gown flowing, standing over a group of African-Americans – in a field, picking cotton.

In all likelihood, few people who enter the courthouse notice this anomaly. But it seems to stand as a signifier for precisely the hypocrisy that Zizek observes, and that Buckley attacks. For in The Light on the Hill, by calling into question the complexities of social life, by demanding social responsibility, Buckley challenges individuals to live according to certain ideals.

I can only think here of the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Nobel-prize winner and author of the Letter from Birmingham Jail. There, Dr. King observed:

There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair.11

These are precisely the same sentiments that Prime Minister Chifley had expressed in 1949. Buckley understands the ongoing need for social change, and the responsibility of artists to create works which challenge dominant paradigms through subtle, complex and purposeful means.

As an ongoing series of installations, The Slaughterhouse Project stands as a suite of works which call into question the roles and responsibilities of cultures to consider and address diverse concerns. Buckley’s recontextualisations – and his ability to recognize the fact that texts are always already readymades – are complex, and both closely and subtly related to the issues his interventions consider. Over the course of more than a decade, Buckley’s works have considered a range of apparently diverse thinkers. Yet each shares a common concern for the freedoms of individuals and the responsibility of communities, cultures and nations.

The Light on the Hill made manifest the universality of social humanism, drawing upon history, text, music, gender, and identity to question each. It stands as a key part of The Slaughterhouse Project, and a unique and thought-provoking installation.12 The challenge of art, as a key aspect of contemporary culture, certainly achieves Chifley’s objective of working towards the betterment of humankind.

- For a detailed reading of Buckley’s works, please refer my essay The Slow Fire, in Brad Buckley, Artspace Publications, Sydney, 2002, as well as the many other excellent essays listed in the monograph’s bibliography. [↩]

- Perhaps the most sustained analyses of this position can be found in Yve-Alain Bois’ Painting: The Task of Mourning, in Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model, MIT Press: Cambridge, 1990, pp. 232 – 235, and Thierry de Duve’s seminal essay The Readymade and the Tube of Paint, which first appeared in Artforum in 1986 and was recently revised and expanded to appear in his Kant After Duchamp, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1999, at pp. 147 – 196. [↩]

- The complete text of Prime Minister Chifley’s speech can be found at the website of the Australian Labor Party, www.alp.org.au/about/light_on_hill.html [↩]

- It is difficult, if not impossible, to extrapolate on the significance and implications of The Light on the Hill without outlining briefly some charcteristics of the larger Birmingham community. In a city of 901,000, 68% are white, 30% are African American or black, and the remainder are are Asian or Hispanic. 78% of Alabamians were born in the state. 25% of the population has a Bachelor’s Degree or higher. 13% of the population lives in poverty, according to the US Census for 2000. [↩]

- Slavoj Zizek, Tarrying with the Negative, Duke University Press: Durham, 1993. See particularly Chapter 6, pp. 200 – 237. [↩]

- For further research on southern slavery, one might consider the research produced by the Federal Writers’ Project between 1936 and 1938 entitled “Slave Narratives.” Further information can be found at memory.loc.gov/ammem/snhtml/snhome.html. [↩]

- One might consider here, particularly, the discussions in Greg Waite’s book Nietzsche’s Corps/e, as considered in Bruce Krajewski’s essay found at http://www.samla.org/sar/01wKrajewski.html. [↩]

- The quote which appears is an edited version. In its entirety, the text is: Tom gave up the brush with reluctance in his face but alacrity in his heart. And while the late steamer “Big Missouri” worked and sweated in the sun, the retired artist sat on a barrel in the shade close by, dangled his legs, munched his apple, and planned the slaughter of more innocents. There was no lack of material: boys happened along every little while; they came to jeer, but remained to whitewash. By the time Ben was fagged out, Tom had traded the next chance to Billy Fisher for a kite, in good repair; and when he played out, Johnny Miller bought in for a dead rat and a string to swing it with – and so on, and so on, hour after hour. And when the middle of the afternoon came, from being a poor poverty-stricken boy in the morning, Tom was literally rolling in wealth. He had beside the things before mentioned, twelve marbles, part of a jews-harp, a piece of blue bottle glass to look through, a spool cannon, a key that wouldn’t unlock anything, a fragment of chalk, a glass stopper of a decanter, a tin soldier, a couple of tadpoles, six fire-crackers, a kitten with only one eye, a brass door knob, a dog-collar – but no dog – the handle of a knife, four pieces of orange peel, and a dilapidated old window-sash. [↩]

- The significance of Negro spirituals and gospel music as a form of information and social activism is well documented. For further information, www.negrospirituals.com stands as a respected reference point. [↩]

- Zizek, ibid., at 1. [↩]

- For the complete text of Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, please visit www.nobelprizes.com/nobel/peace/MLK-jail.html [↩]

- The installation proved too complex for certain viewers not used to installation projects. One gentleman remarked, after having been in the gallery for some time, that it was “looking good for the next show”, and was puzzled to learn that he was in fact looking at the show. [↩]